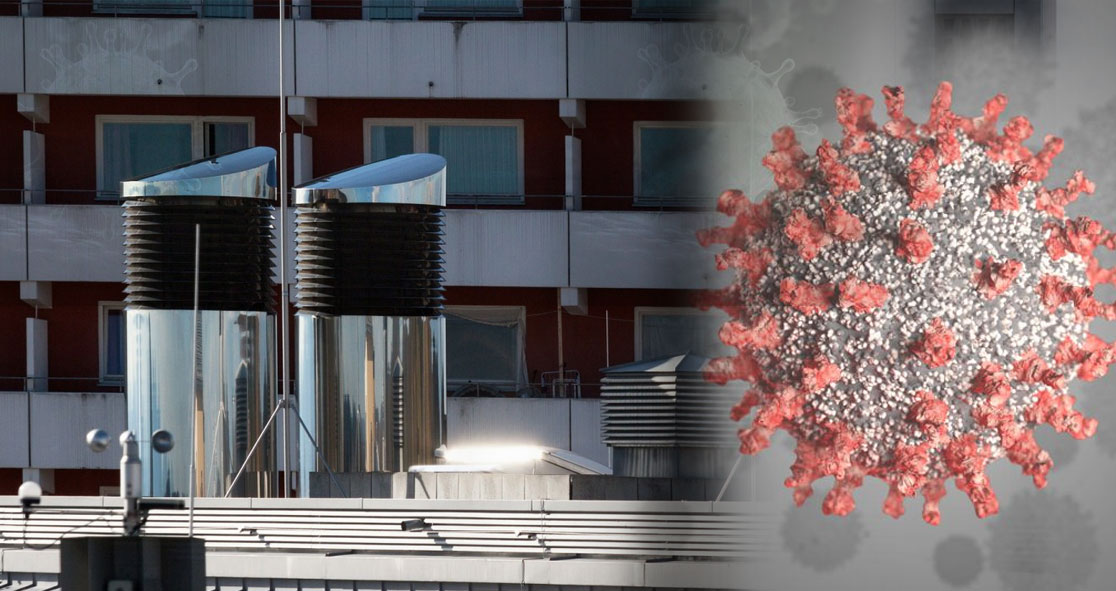

A new study, published in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics, has suggested that many ventilation systems, which keep temperatures comfortable and increase energy efficiency, could increase the risk of COVID-19 exposure, especially during the coming winter,

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have found that ‘mixing ventilation’ systems, which keep conditions uniform in every part of the room, disperse airborne contaminants evenly throughout the space, such as droplets and aerosols that may potentially contain viruses.

There is growing evidence that the new coronavirus can spread through larger droplets and smaller aerosols, which are expelled when people cough, sneeze, laugh, talk or even breathe.

Besides, studies have found that indoor transmission is much more common than outdoor transmission, increasing the risk of exposure.

Lead author Prof. Paul Linden said, “As winter approaches in the northern hemisphere and people start spending more time inside, understanding the role of ventilation is critical to estimating the risk of contracting the virus and helping slow its spread.”

“While direct monitoring of droplets and aerosols in indoor spaces is difficult, we exhale carbon dioxide that can easily be measured and used as an indicator of the risk of infection,” he added.

“Small respiratory aerosols containing the virus are transported along with the carbon dioxide produced by breathing, and are carried around a room by ventilation flows,” Prof. Linden continued. “Insufficient ventilation can lead to high carbon dioxide concentration, which in turn could increase the risk of exposure to the virus.”

Climate change has accelerated since the last century, which is why buildings are built by keeping energy efficiency in mind. However, in the past few years, reducing indoor air pollution has become the main concern for designers of ventilation systems.

Study author Dr. Rajesh Bhagat said, “These two concerns are related, but different, and there is tension between them, which has been highlighted during the pandemic. Maximizing ventilation, while at the same time keeping temperatures at a comfortable level without excessive energy consumption is a difficult balance to strike.”

Prof. Linden said, “In order to model how the coronavirus or similar viruses spread indoors, you need to know where people’s breath goes when they exhale, and how that changes depending on ventilation. Using these data, we can estimate the risk of catching the virus while indoors.”

“You can see the change in temperature and density when someone breathes out warm air — it refracts the light and you can measure it,” Dr. Bhagat said. “When sitting still, humans give off heat, and since hot air rises, when you exhale, the breath rises and accumulates near the ceiling.”

The team found that facemasks are effective at reducing the spread of exhaled breath, and eventually droplets.

Prof. Linden explained, “One thing we could clearly see is that one of the ways that masks work is by stopping the breath’s momentum.”

“While pretty much all masks will have a certain amount of leakage through the top and sides, it doesn’t matter that much, because slowing the momentum of any exhaled contaminants reduces the chance of any direct exchange of aerosols and droplets as the breath remains in the body’s thermal plume and is carried upwards towards the ceiling,” he added.

“Additionally, masks stop larger droplets, and a three-layered mask decreases the amount of those contaminants that are recirculated through the room by ventilation.” “Keep windows open and wear a mask appears to be the best advice,” Prof. Linden recommended. “Clearly that’s less of a problem in the summer months, but it’s a cause for concern in the winter months.”