Previous research has shown that cancer cells produce large quantities of lactic acid (lactate), which disrupts our defense against tumors. However, experts did not know exactly how this happens.

Now, Prof. Jo Van Ginderachter of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel and the Flemish Institute for Biotechnology has found the answer.

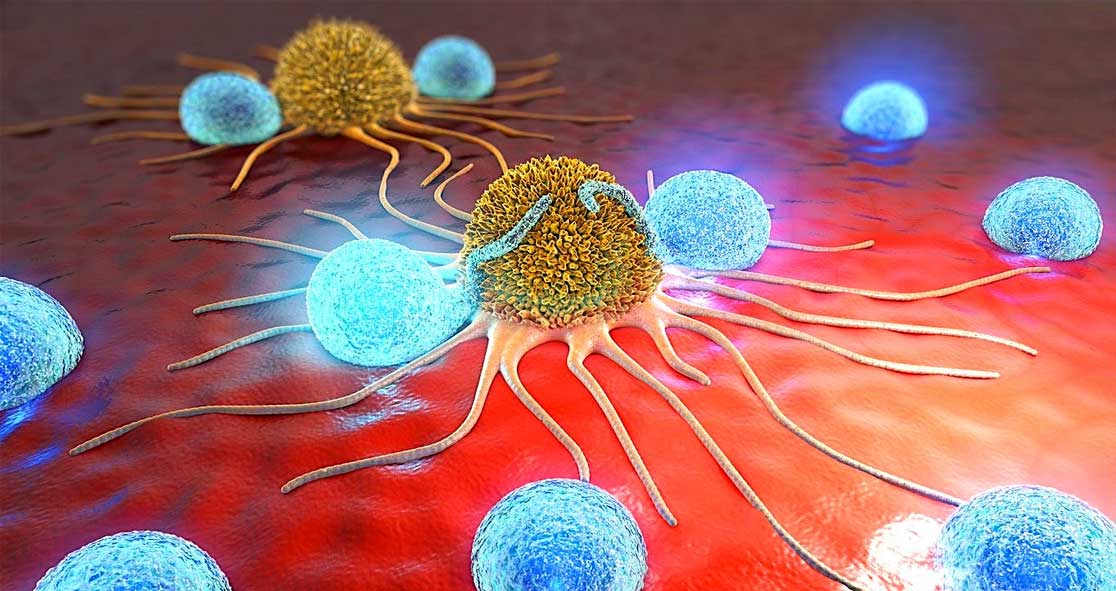

Prof. Van Ginderachter, who is an immunologist and cancer researcher, said, “We found that macrophages, a specific type of immune cells, use lactic acid as a source of energy. Macrophages are present in large numbers in tumors but are, as it were, misled by the tumor in order to help it grow.”

“With the lactic acid of the cancer cells, the macrophages keep themselves alive but eventually develop into tumor-promoting cells,” he added. “Under the influence of the lactic acid, the macrophages paralyzes other ‘killer’ immune cells that can recognize and destroy the cancer cells, thereby helping to weaken the tumor immunity.”

In addition, the macrophages eventually contribute to the resistance of tumors to immunotherapy.

“This strong presence of lactic acid in tumors can have consequences for immunotherapy,” explained Prof. Van Ginderachter says.

“In immunotherapy, our body’s own ‘killer’ immune cells are triggered to optimally attack cancer cells,” he noted. “Although this therapy is very promising and works very well for skin cancer and is increasingly used for lung cancer, for example, the reality remains that only a proportion of patients respond favorably to it.”

“One of the reasons is probably that macrophages feed on the lactic acid in the tumor and, as a result, switch off the ‘killer immune cells’ that you want to stimulate through immunotherapy,” Prof. Van Ginderachter added. “So we need to be able to suppress immune-disrupting cells, such as the macrophages, and still increase the success of immunotherapy.”

Therefore, it is important to look at how the formation of lactic acid in tumors can be curbed.

Prof. Van Ginderachter pointed out that lactic acid occurs in large quantities in many different tumor types.

He said, “Cancer cells typically produce a lot of lactic acid. And in tumors, you also have regions with a very low oxygen concentration, in which lactic acid can be raised to even higher levels. You can try to prevent the production of lactic acid in tumors.”

“This is a strategy that is already being investigated in first-stage clinical trials. However, precisely because we know that in addition to cancer cells, many other cells in the tumor produce lactic acid, it remains to be seen whether these strategies will be sufficient to reduce the lactate to such an extent that its effect on the tumor-supporting macrophages is nullified.”

“On the other hand, one can try to neutralize lactic acid, for example, by administering a kind of buffer solution,” he explained. “Preliminary research on this is also underway. Another option is to use chemicals to ensure that macrophages can no longer feed on the lactic acid. It is important that such a substance is not toxic and that it makes its way to the tumor in a targeted manner.”

“Research is also being carried out in our laboratory into these problems, so that future medicines can be delivered directly to the tumor or the macrophages, thus avoiding side effects,” Prof. Van Ginderachter added.

Other researchers who were part of the study were Xenia Geeraerts, Prof Sarah-Maria Fendt, and Prof Jan Van den Bossche of the University of Amsterdam. The findings were published in the journal Cell Reports.