An ultrashort-pulse laser, developed by the researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, has been found to be effective at killing multidrug-resistant bacteria, without damaging human cells, according to MedGadget.

The researchers hope that the laser, which works by vibrating and breaking protein structures within the bacterial cell, could decontaminate wounds and blood products.

Most antibiotics are no longer effective and killing multidrug-resistant bacteria has become tricky. General antibacterial strategies to kill such bacteria include heat or applying bleach, but they are not safe to use within the human body.

The researchers developed a laser technology that can kill these microbes with ease, without harming human cells.

Lead author Dr. Shaw-Wei Tsen said, “The ultrashort-pulse laser technology uniquely inactivates pathogens while preserving human proteins and cells. Imagine if, prior to closing a surgical wound, we could scan a laser beam across the site and further reduce the chances of infection.”

“I can see this technology being used soon to disinfect biological products in vitro, and even to treat bloodstream infections in the future by putting patients on dialysis and passing the blood through a laser treatment device,” he added.

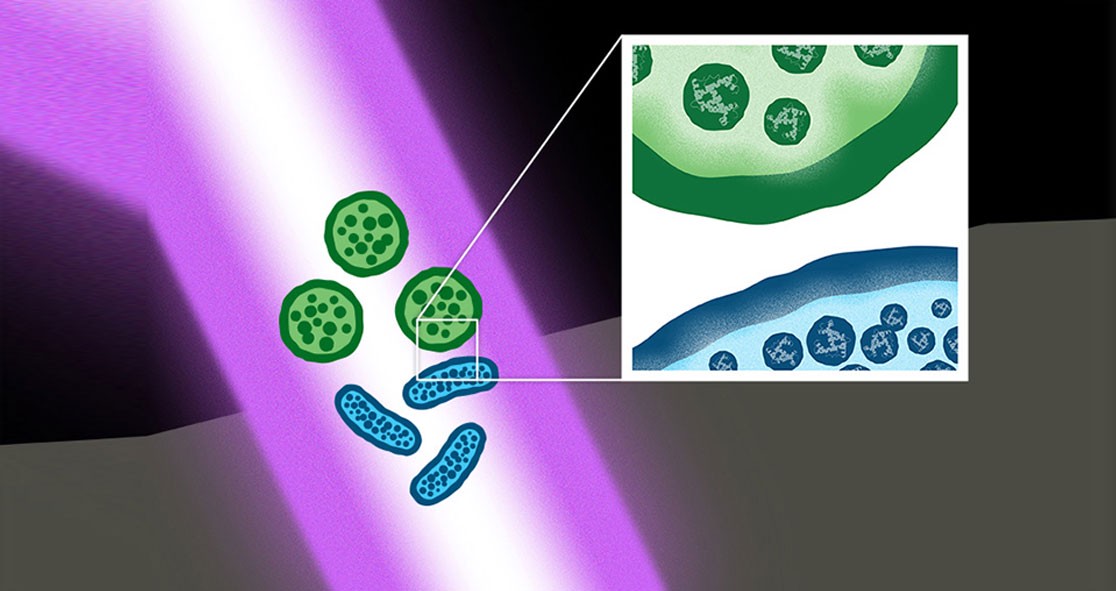

The new technology works by disrupting protein structures in the cells of bacteria, eventually leading to cell death. In addition, the researchers found that human cells are not affected at the laser power levels required to kill the cells of bacteria and viruses.

Dr. Tsen explained, “We previously published a paper in which we showed that the laser power matters. At a certain laser power, we’re inactivating viruses. As you increase the power, you start inactivating bacteria. But it takes even higher power than that, and we’re talking orders of magnitude, to start killing human cells. So there is a therapeutic window where we can tune the laser parameters such that we can kill pathogens without affecting the human cells.”

The researchers have tested the laser technology on multidrug-resistant bacteria in the lab and demonstrated that 99.9% of the bacterial samples were killed.

“Anything derived from human or animal sources could be contaminated with pathogens,” noted Dr. Tsen. “We screen all blood products before transfusing them to patients. The problem is that we have to know what we’re screening for.”

“If a new blood-borne virus emerges, like HIV did in the ’70s and ’80s, it could get into the blood supply before we know it,” he added. “Ultrashort-pulse lasers could be a way to make sure that our blood supply is clear of pathogens both known and unknown.”