Scientists from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have discovered a specific gene’s previously unknown role in fertility issues and early menopause.

A study, published last month in the journal Science Advances, found that fruit flies, roundworms, zebrafish, and mice were found to be infertile because they lacked that gene. The study also found a link between mutations in this gene and early menopause.

The gene, called nuclear envelope membrane protein 1 (NEMP1), has not been studied much. In animals, mutations in this gene had been associated with impaired eye development in frogs.

Senior study author Dr. Helen McNeill said, “We blocked some gene expression in fruit flies but found that their eyes were fine. So, we started trying to figure out what other problems these animals might have. They appeared healthy, but to our surprise, it turned out they were completely sterile. We found they had substantially defective reproductive organs.”

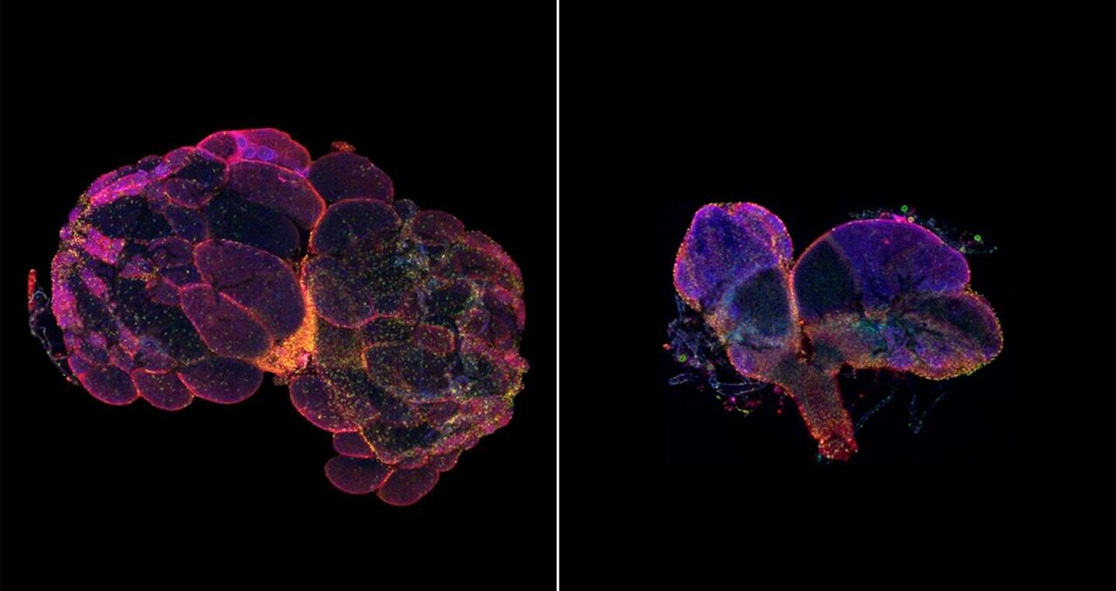

Both males and females had fertility issues when this gene was missing, especially in females, the team found that the gene envelop contains the egg’s nucleus, which looked like a floppy balloon.

Dr. McNeill explained, “This gene is expressed throughout the body, but we didn’t see this floppy balloon structure in the nuclei of any other cells. That was a hint we’d stumbled across a gene that has a specific role in fertility.”

“We saw the impact first in flies, but we knew the proteins are shared across species,” she added. “With a group of wonderful collaborators, we also knocked this gene out in worms, zebrafish, and mice. It’s so exciting to see that this protein that is present in many cells throughout the body has such a specific role in fertility. It’s not a huge leap to suspect it has a role in people as well.”

“It’s interesting to ask whether stiffness of the nuclear envelope of the egg is also important for fertility in people,” Dr. McNeill continued. “We know there are variants in this gene associated with early menopause. And when we studied this defect in mice, we see that their ovaries have lost the pool of egg cells that they’re born with, which determines fertility over the lifespan.”

“So, this finding provides a potential explanation for why women with mutations in this gene might have early menopause. When you lose your stock of eggs, you go into menopause.”

She went on to explain, “If you have a softer nucleus, maybe it can’t handle that environment. This could be the cue that triggers the death of eggs. We don’t know yet, but we’re planning studies to address this question.”

Dr. McNeill and her team found only one other problem with the mice missing this gene. They were anemic, meaning they lacked red blood cells.

She explained, “Normal adult red blood cells lack a nucleus. There’s a stage when the nuclear envelope has to condense and get expelled from the young red blood cell as it develops in the bone marrow. The red blood cells in these mice aren’t doing this properly and die at this stage. With a floppy nuclear envelope, we think young red blood cells are not surviving in another mechanically stressful situation.”

“We can direct these stem cells to become eggs and see what effect these mutations have on the nuclear envelope,” Dr. McNeill continued. “It’s possible there are perfectly healthy women walking around who lack the NEMP protein.” “If this proves to cause infertility, at the very least this knowledge could offer an explanation. If it turns out that women who lack NEMP are infertile, more research must be done before we could start asking if there are ways to fix these mutations — restore NEMP, for example, or find some other way to support nuclear envelope stiffness.”