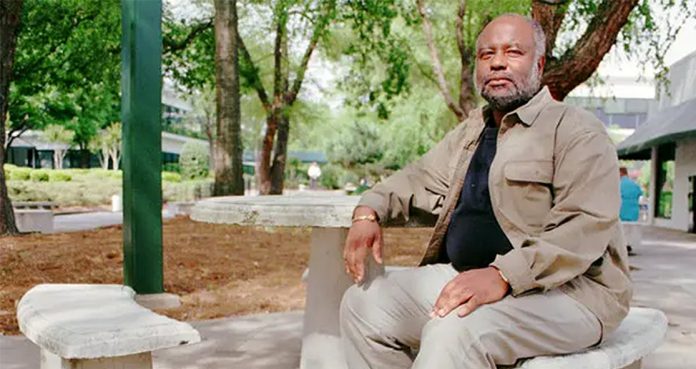

Bill Jenkins has died at the age of 73. He was a famous epidemiologist who helped in terminating the notorious, unethical and racist Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

He passed away on February 17 in Charleston, South Carolina. The Morehouse School of Medicine, where he worked for many years, confirmed his death.

In the mid-1960s, he came across one of the darkest chapters in the United States’ medical history – the Tuskegee syphilis study.

Jenkins played a pivotal role in revealing the study to the public. He showed his outrage over the racism involved in the Tuskegee syphilis study in an effort to prevent and reduce racial disparities and injustice in health care.

The epidemiologist noted that the study actually was started with good intentions to tackle syphilis in the early 20th century. The U.S. Public Health Service collaborated with the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama to conduct a study in 1932 amid skyrocketing crates of syphilis.

The experiment offered free medical exams, meals as well as burial insurance to enroll 600 black men, 201 of whom did not have syphilis.

Jenkins recalled that initially, the experiment would follow the untreated men for at least a year; however, four years later, researchers decided to follow them until death. Surprisingly, the participants were not informed about the investigation. Moreover, men who had syphilis were kept untreated even when penicillin was made available to cure the disease.

Unfortunately, men who were left untreated passed this contagious disease to their wives who eventually passed it to their children.

Jenkins said he came across the study in 1968 and worked with his fellow epidemiologist, Peter Bauxum, to stop the study.

Until 1972, the study did not end after congressional hearings were held. An advisory panel was appointed to review the experiment. It was found that the knowledge gained was scarce when compared with the risks the study posed on the subjects.

A class action litigation quickly followed, resulting in a $10 million settlement and compensation for all the living participants, their wives and children. They were also provided medical benefits and burial services.

In 1997, President Bill Clinton formally apologized for the experiment, expressing regret that the federal government conducted a study that was so clearly racist.

According to the CDC, the last participant of the study died in 2004 and the last widow, who received medical benefits, died in 2009. As of 2015, there were 12 offspring of the participants receiving medical benefits.

Jenkins went on to take care of the participants by serving as the manager of the Participant Health Benefits Program, offering medical services to them.

Starting from 1980, he went on to work for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for HIV, STD and TB Prevention.

Jenkins did the Master of Public Health program at the Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta in 1995.

Throughout his life, he remained a vocal advocate for preventing and reducing racial health disparities and discrimination in health care.

“It is the only health condition where we want to study the symptom – race – rather than the ideological factor – racism. It’s amazing to me as an epidemiologist. To solve health disparities, we must also study racism.” Jenkins said in the American Public Health Association speech. A Quaker service has been arranged for Jenkins on March 23 in Decatur, Georgia.