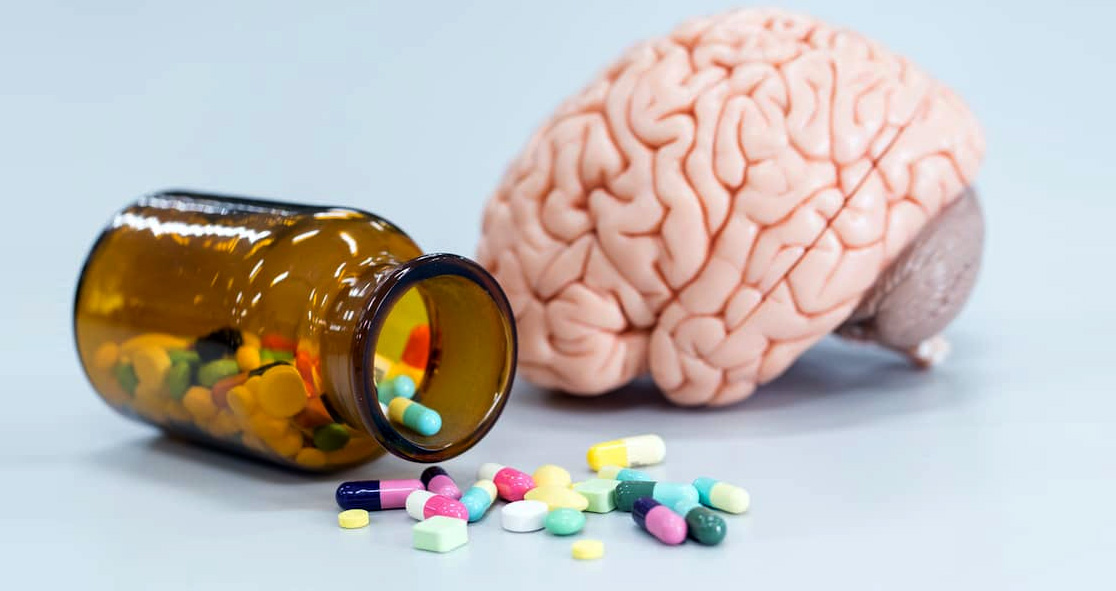

Smart drugs, or nootropics, are pharmaceutical cognitive enhancers (PCEs) that are often used by healthy people to boost their memory, motivation, concentration, focus, and attention.

Off-label use of these drugs has increased as they have been found to enhance productivity, efficiency, and performance – the features that are highly valued in modern society. Smart drugs are also used to promote learning, clarify thinking, increase mood, improve temperament, and maximize motivation.

Nootropics are regulated medicines prescribed for the treatment of narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, Alzheimer’s disease (dementia), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and schizophrenia.

But, is an off-label use of smart drugs ethical?

Using prescription smart drugs for non-medical purposes has caused some controversy over cognitive enhancement. As far as ethical issues are concerned, the non-medical use of smart drugs deserves an in-depth discussion.

It is a fact that taking smart drugs is already something very common in today’s professional and social groups. Therefore, we need a more stringent regulation when it comes to regulating the global smart drugs market, where it is possible to find substances of questionable composition, quality, and purity.

Many people buy smart drugs from unregulated sources, raising concerns over the purity, safety, and efficacy of the drugs. Such drugs do not benefit anyone, rather they harm those who get them through foreign providers and without medical supervision.

So, there is a need for an establishment of a legal market to control and monitor the actual purity, safety, and efficacy. It is also necessary to regulate the market’s scope, and identify safe and efficient use of smart drugs to address the ethical issues.

Prof. Barbara Sahakian, Professor of Clinical Neuropsychology at the University of Cambridge, discussed the emergence of smart drugs and the ethical issue they raise.

She said she had many ethical discussions with the public on the use of PCEs by healthy people.

“A variety of views have emerged, ranging from ‘These drugs should only be used by people with neuropsychiatric disorders such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, or Alzheimer’s Disease’, to ‘If they are safe, why not use them, to make up for fatigue, to improve memory or other forms of cognition?’, and ‘Why not use them to get in an especially productive working day?’ she said.

Prof. Sahakian, who is has been researching PCEs for over a decade, said, “This increasing lifestyle use has to be balanced against other important facets of life, such as a good work/life balance. The possibility to accelerate into a 24/7 society for many people is a serious concern, as are issues of cheating and coercion.”

She expressed concerns over the non-medical use of these drugs by healthy children and teenagers where their brains are still in development.

“Furthermore, the purchasing of prescription medication over the internet is dangerous,” she added. “However, if long-term safety and efficacy are proven in healthy people, it may well be, at least for certain segments of the population, these drugs will prove life-savers.”

It is still unclear whether the prohibition of smart drugs can be effectively enforced. As smart drugs use becomes widespread among students, discussion on ethical issues will become more pressing in the years to come, according to PubMed.